A Search for Simplicity in a Complex Landscape

We live in an era where scientific discovery often moves faster than consensus. Nowhere is this more evident than in the field of aging research—a domain rich with breakthrough insights but still lacking a unifying framework. What exactly is aging? Can it be defined by a single root cause, a molecular keystone upon which all other symptoms and dysfunctions rest? Or is it more accurately described as a tapestry of interwoven processes, each contributing to the wear and tear we experience over time?

In a recent perspective published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Dr. Jesse Poganik and Professor Vadim Gladyshev of Harvard Medical School grapple with this very question. Their position is clear: the field of geroscience needs a common language and shared conceptual framework—not only to advance research but also to ensure responsible application and communicationindex (7).

Their inquiry dives deep into one of the most philosophically rich and biologically tangled debates of our time: is there a single “essence” of aging?

The Funding and Focus Gap: Why This Matters

Before delving into biology, it’s important to recognize the practical problem this conversation addresses. According to Poganik and Gladyshev, a full 60% of funding from the U.S. National Institute on Aging is allocated to Alzheimer’s disease, rather than aging as a broader phenomenonindex (7). Why? Because aging itself remains poorly defined—scientifically, medically, and legally.

Without a clear definition or central theory, aging is difficult to treat, harder to regulate, and nearly impossible to standardize across clinical trials. This vacuum of clarity leaves room for pseudoscience to flourish, from dubious anti-aging supplements to exaggerated claims in biotech marketing.

The authors argue that establishing a unifying essence of aging—even if it’s just a conceptual one—could help align funding, foster more meaningful collaboration, and protect public trust.

The Cancer Analogy: A Useful Comparison?

One metaphor offered by the authors compares aging to cancer. While cancer is a complex set of diseases, most forms are rooted in a common mechanism: genetic mutations. Though each cancer may behave differently, this shared cause allows for targeted research, regulatory clarity, and clinical pathways.

Could aging have an equivalent? Is there a mutation-like culprit—a biochemical first domino—that sets the aging cascade in motion?

This is the intellectual crux of their question: can we distill aging into a singular explanatory feature that gives rise to all others?

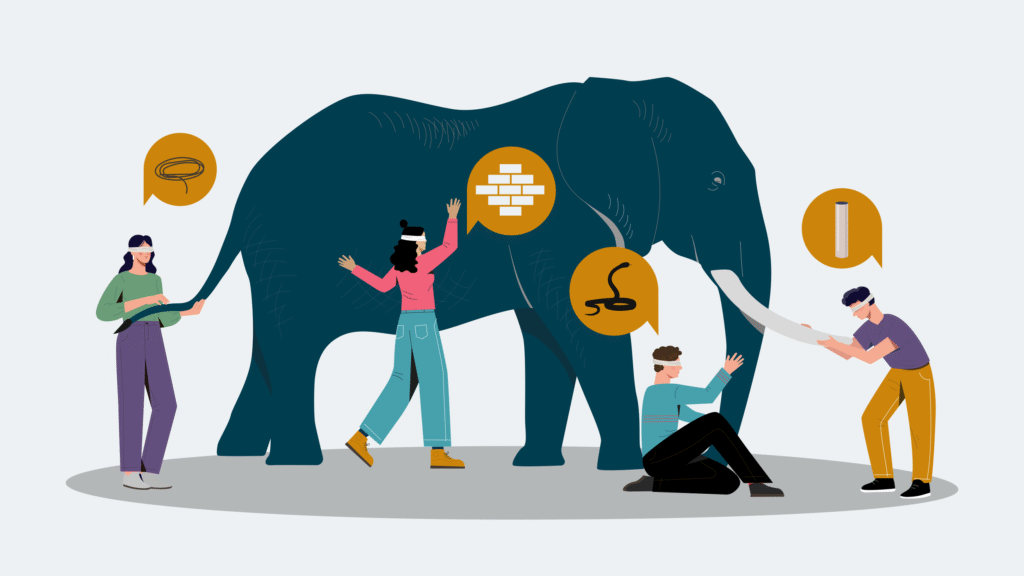

The Blindfolded Elephant: Aging’s Complexity in Perspective

The search for a singular cause of aging is reminiscent of the ancient parable of the blindfolded individuals trying to describe an elephant, each touching a different part. One describes a tail, another a trunk, another a leg—but none perceive the full animal.

Aging is similarly deceptive. Researchers studying genomic instability may see mutations as central. Others focused on inflammation might see immune dysregulation as the key driver. Still others may point to mitochondrial dysfunction, telomere shortening, or epigenetic drift.

Each perspective offers part of the truth—but no single lens captures the entirety of the processindex (7).

Damage, Entropy, and Biological Wear

If there is an overarching force in aging, the authors suggest it might be something as broad—and blunt—as “damage over time” or entropy. These ideas align with the classic view that aging is essentially the accumulation of molecular errors, cellular degradation, and systemic inefficiency.

But damage and entropy, while philosophically compelling, are not clinically actionable. You can’t create a targeted drug to “reverse entropy,” nor can you develop a gene therapy to undo every form of cellular wear and tear at once.

Even if all aging results from damage, that damage is heterogeneous: lipids oxidize, proteins misfold, DNA breaks, cells stop dividing, and tissues scar. Each type of damage requires its own intervention, much like different parts of a car need different types of repairindex (7).

The Programmatic Hypothesis: Aging as a Biological Script

On the other side of the spectrum lies the programmatic theory of aging. This view holds that aging is not just a breakdown, but a side effect of developmental or evolutionary programs that are switched on or left running too long.

For instance, some pathways that promote growth early in life—like mTOR or IGF-1—may continue to operate later in life, where they contribute to diseases like cancer or diabetes. In this view, aging is a kind of biological overreach, a software glitch in the machinery of life.

While intriguing, this perspective also faces practical limitations. Programmatic causes must be identified and targeted individually, much like the damage-based hallmarks. And like damage, programs are not universal: what’s overactive in one tissue might be underactive in anotherindex (7).

Aging as a Collection, Not a Category

Rather than looking for a single root cause, perhaps it’s more realistic—and more useful—to view aging as a collection of interdependent processes.

The “Hallmarks of Aging” model, originally proposed in 2013, embraces this idea. It outlines multiple core mechanisms—genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, and more—that contribute to aging in parallel. Importantly, these hallmarks interact with and amplify each other, making aging a systems-level phenomenon rather than a linear one.

This networked view aligns more closely with real-world biology: complex, dynamic, and context-sensitive.

Clinical Implications: A Mosaic of Targets

If there is no “one aging to rule them all,” then effective intervention will require multiple strategies working in concert.

For example:

- Senolytics aim to eliminate senescent cells—those that have stopped dividing but remain metabolically active and pro-inflammatory.

- Epigenetic reprogramming seeks to restore youthful gene expression patterns.

- Caloric restriction mimetics attempt to replicate the longevity benefits of fasting without dietary change.

- Mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants focus on restoring energy metabolism.

Each approach tackles a different “part of the elephant.” Together, they may form a therapeutic mosaic capable of meaningfully extending healthspan.

This multi-pronged model also opens the door to personalized longevity medicine—where treatments are matched to an individual’s unique aging profile, much like precision oncology tailors therapy to a tumor’s genetic makeup.

The Value of Conceptual Clarity

While a single biological essence of aging may be elusive, that doesn’t mean the search for clarity is futile. On the contrary, conceptual frameworks still offer immense value.

They help:

- Unify research agendas

- Guide funding priorities

- Standardize clinical endpoints

- Communicate science to the public and policymakers

A clear, shared language could also shield the field from pseudoscience and overhyped commercial claims—a major concern raised by Poganik and Gladyshevindex (7).

A Way Forward: Collaboration Without Oversimplification

The authors conclude with a call for collaboration, not just across disciplines but across perspectives. Whether one studies DNA methylation, immune resilience, senescence, or bioelectric signaling, each angle has something to contribute.

However, collaboration requires shared goals and defined targets. If aging is accepted as a heterogeneous process, then researchers must identify intervention points that are clear, measurable, and relevant across disciplines—even if they’re not universal.

Aging, in this view, is like a symphony: no single instrument carries the melody, but each plays a role in the greater composition.

Final Reflections: Toward a Practical Philosophy of Aging

So, is there a single essence of aging?

Scientifically speaking, probably not. But that’s not a weakness—it’s a reflection of life’s incredible complexity. Aging is not a bug in the system; it may be the system itself adapting, evolving, and responding to countless inputs over time.

From a wellness perspective, this means we should embrace plurality in prevention:

- Support mitochondrial function

- Reduce inflammation

- Protect DNA integrity

- Cultivate hormonal balance

- Promote regenerative capacity

Instead of waiting for a single miracle cure, we can make meaningful strides today—layer by layer, habit by habit, intervention by intervention.

Aging may be multifactorial, but thriving through it can be intentional.